I finished reading Ernst Jünger's WWI memoir Storm of Steel recently. I decided to really lean into it and bought the extra-edgy translation from Passage Press, which is the version that was translated from German to English in 1929 and includes lots of Jünger's original reflections on the war rather than just the series of events that happened to him. Mostly you can see overtures of German nationalism and ideas that would eventually contribute to and influence the Nazis.

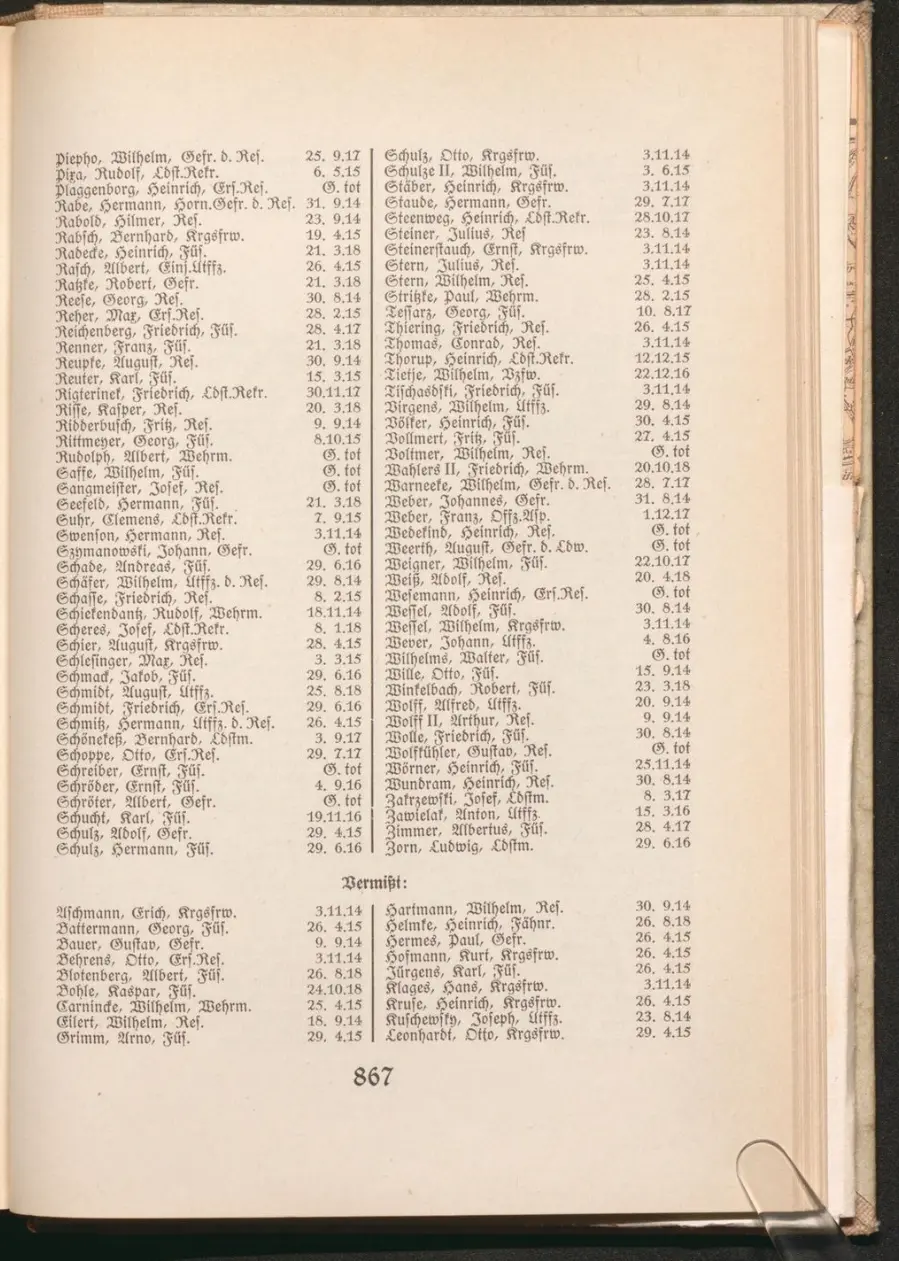

Why am I reading one of Hitler's favorite books? Well, I got into ancestry and found out I have a 3rd great-grand uncle who was in the 73rd Hannoverian Fusiliers, 8th company, and would have been under the command of Jünger, who was a lieutenant in the 73rd. My great-uncle's name was Albertus Janssen Zimmer and he died April 28, 1917 in the Battle of Arras along with most of what remained of 8th company by then.

Ancestry is a business sector that I think will have secular tailwinds that never end. If one of the viable theories for existence is a near-infinite ancestor simulation, ancestry likely has a strong bull case for continued TAM growth. I bought a fancy premium subscription to Ancestry.com, which was acquired by Blackstone private equity in 2020 for $4.7 billion. Ancestry.com's UI is pretty terrible—lots of unnecessary clicking and overly focused on the family tree views—but what it does have is a very impressive dataset of original source document scans and a pretty great OCR implementation that can pull text out of them. When you pair this with AI you can do lots of interesting self-directed research. I think ditching the family tree view in favor of a contextualized map visualization paired with some speculative/narrative AI storytelling would be a pretty compelling change. Anecdotally it seems like most of the users of Ancestry.com are quite old, 60+, and are completionists—they want to fill out an entirely correct family tree as far back as they can (including fabricating a nobility connection). Ancestry should be a hobby for young people, who can still actually talk to their ancestors. Hear the oral tradition and then compare it to the primary source documents. Have AI help expand that narrative with its own speculations/hallucinations. The only reason I found this connection from my great-uncle Albertus and Jünger was that ChatGPT offered it up and then helped me track down source documents to get a better picture of when and how Albertus died.

When you get into ancestry you're going to start caring a lot about primary sources—things like census and church records. But the most interesting stuff will be the letters and stories from the people who were there. Stories can be controversial: whose personal experience is the correct one? I remember reading some excerpts of All Quiet on the Western Front in high school and being prodded by the teacher to write an essay on how terrible WWI was. All Quiet is a mostly fabricated story loosely based on the experiences of its author, Erich Maria Remarque, who eventually had to flee Germany after being marked as a traitor by the Nazis. Storm of Steel on the other hand is an autobiographical memoir, what historians would consider primary source material told by Ernst Jünger, who would become one of the most decorated German war heroes of WWI and considered a national treasure by the Nazis.

A long period of law and order, such as our generation has behind it, produces a real craving for the abnormal, a craving that literature stimulates.

The long period of law and order Jünger is referring to would be the German unification led by Otto von Bismarck—the German golden age. My great-uncle Albertus's parents, Gerd and Elisabeth, lived through this time period. They were Ostfriesen, people who lived in East Frisia, a distinct ethnic group who spoke their own dialect of German, Seeltersk. Gerd did live in a period of law and order but at the same time, despite never moving from his hometown, was ruled by 5 different governments and had 7 different monetary standards. This period of law and order is mostly just the period of the formation of the German national identity. The wars of German unification followed by the social reforms of Bismarck are what helped what would otherwise be considered Prussia turn into Germany. Gerd and Elisabeth clearly didn't buy into this new nation and so would pay to send every son of theirs over to America, specifically Minnesota, before they were eligible for the German draft. It wasn't until their youngest son (Albertus) that for some reason they chose not to—maybe Albertus wanted to stay, maybe Gerd and Elisabeth wanted a son to help look after them in old age.

Anecdotally in the early 1900s it seemed like Germany was the new rising power, much like China might be viewed today. At the same time, immigration to America was no longer as appealing: no more free land and also an increase in anti-immigrant sentiment. To a young Albertus who grew up in Bismarck’s newly formed nation, it might have seemed obvious to stay instead of moving to a new place. There was a meaningful difference in outcomes for his older brothers based on how early they immigrated—the earlier the better—and also who they ended up marrying in America. The best possible outcomes came from marrying the daughter of a landowner without any sons. That advice is still true today for any enterprising young man: marry the daughter of rich parents who don't have any sons. Anyways, it's impossible to say for sure why Albertus stayed in Germany, only speculation.

Ernst Jünger was a lieutenant, the equivalent of a military middle manager, and who by his own admission was a thrill seeker. I read his book not because I am a fan-boying right-winger (though the fact I have an ancestor who served with Jünger gives me more street cred than the current batch of trad-cath/jew conservatives) but because it's a good primary source for the death of my great-uncle Albertus. While I definitely can't throw stones at the most decorated German veteran of WWI, I can't help but notice that the Peter Principle might be particularly applicable to the Kaiser's military and particularly to Jünger. You see, Jünger was supposed to be running a communication post when Albertus died.

At 7am I received a message by light-signal addressed to the 2nd Battalion: "Brigade requires immediate report on the situation." After an hour a despatch-carrier brought back the news: "Enemy taken Arleux and Arleux park. Ordered 8th Company to counter-attack. No news so far. Rocholl, Captain."

This was the only message that my tremendous apparatus of transmission had to deal with during all three weeks of my time in Fresnoy—though certainly it was a very important one. And now that my activity was of the utmost value, the artillery fire had put nearly the whole organization out of action. Such were the results of over-centralization.

This surprising information explained why we had heard rifle-bullets fired at no very great range, clattering against the walls of the houses.

We had scarcely realized the great losses suffered by the regiment.

There was no news about the 8th company's counterattack because it failed. The lieutenant commanding the 8th was quickly shot in the head after hopping out of the German trench, and the rest of the company was trapped in no-man's land while having grenades thrown at them by the 90th Winnipeg Rifles (Canadian Expeditionary Force 8th Battalion). I don't know how Albertus died for sure, other than his body was never recovered. He might have been atomized by an English artillery shell that precipitated the original Canadian charge. He could have died valiantly fighting off Canadian shock troops to the bitter end, or just executed by them while begging to be taken prisoner. Either way Jünger was less than 500m away, ostensibly manning a communications post while also failing to relay any communications. This being a neat victory for the Canadians means it has a nice little article on the Canadian government’s website.

Jünger's writing style is more nuanced about criticizing German leadership than what would be normal today. Just the fact that he mentions that Captain Rocholl ordered the doomed counterattack is enough for us to get a clear picture: Brigade asked 2nd Battalion (led by Captain Rocholl) what’s going on that's causing all the problems, Captain Rocholl, wanting to demonstrate some sort of action, orders a doomed counterattack and relays that message back to Brigade, a couple dozen boys die pointlessly, and the rest is history. I'm not really a military history buff by any means but Captain Rocholl is often described by Jünger as more of the old-guard stodgy, grand-strategy driven leaders. A commander who’s maybe more focused on going through the performance of being at war rather than winning it? Annecdotaly the only picture of Captain Rocholl in the regimental history book is of him riding a horse in parade, interpret that as you will.

Jünger also briefly directly commanded Albertus's 8th battalion when they had been reconstituted after being annihilated at the Somme. This batch included Albertus, who would have joined along with 179 other men when the unit was reconstituted, only to be annihilated again just three months later when he died. By April 28 of those 180, only 40 would remain. Albertus made it longer than most. Jünger describes this group in one passage:

I ran through the trench, but not a soul did I see till I came to a deep dugout, where a group of men crowded on the steps like hens crowding together in the rain, with no one in command.

20 year old Albertus might have been one of those hens, commandless, sheltering from English artillery barrage. Maybe Jünger’s leadership skill instilled the necessary confidence that would eventually help those hens charge headfirst into their death at the hands of Canadian shock troops?

We stand for what will be and for what has been. Through force without and barbarity within conglomerate in somber clouds, yet so long as the blade of a sword will strike a spark in the night may it be said: Germany lives and Germany shall never go under.

The irony for me of reading Storm of Steel is that Gerd and Elisabeth's daughters all stayed in Germany, married, and had children. Gerd and Elisabeth's grandsons fought in WWII both for the United States and for the 3rd Reich; all their German grandsons died in WWII and as far as I can tell there are no more German descendants while there are now hundreds of American descendants. Germany did in fact go under but its people found a way to survive its death. The paper trail of Gerd and Elisabeth goes dark after WWI. The last primary source I found was a passenger list that has Gerd arriving in the US in 1922, and uncited sources that he died in 1925 and Elisabeth in 1938. My grandma thinks they did end up immigrating but if that's true then it was illegally.

“White people have no culture” was (maybe still is?) a popular pejorative for non-whites (and self-loathing whites) to throw around. I think formally the critical theory argument behind it is that whiteness was a top-down manufactured concept created to collapse European ethnic differences into a single identity. I personally have no connection to East Frisians; I know nothing about them, the language, their traditions. Fewer than 3,000 people today even speak Seeltersk. There was never a possible future where my ancestors would’ve retained their culture—just a choice about being assimilated into Prussian/German culture or to go somewhere else. This gets to what really is the bar for becoming a naturalized American citizen: total annihilation of your old culture. The only remittances you send back are in the form of explosives. This is why becoming an American today is harder than ever, nothing to do with skin color but the fact that we have instant global communications, instant global value transfers and you can fly anywhere in the world for a couple hundred bucks. You don't have to surrender any of your old cultural traditions, your old language, your old friends and family. This is not a feature but a bug. It has and will create social dysfunction as time goes on.

Worth Reading?

It’s better than All Quiet on the Western Front but probably less engaging than whatever AI slop smut novel is currently trending. Another potential turn-off could be some of the insecure bluster that any gifted early 20s middle manager is going to have—but if you're old enough to smile at it you'll enjoy the read. If you want to avoid the early 20s nationalistic bluster, his later books might be more interesting. I've started reading Eumeswil, which he published in 1977 and is a memoir disguised as a fiction novel.