I just came back from a 5-day bikepacking trip around Las Cruces, New Mexico. Going on a bikepacking trip in a desert during the Michigan winter is becoming a bit of a habit. One that I hope I can keep up for a while. Nothing purges the seasonal affective disorder quite like the desert sun.

I'm definitely not a good cyclist; I'm at around 2-3 Watts per kilo, which is solidly a novice-level power-to-weight ratio. I'm 6'2", ~230 lbs, with broad shoulders, a big ol' torso, and short legs. I'm not interested in going on group rides, racing, or grinding on a trainer all winter. I almost never do any road riding, where especially in the Midwest you're only one angry, buzzed driver away from meeting God a few decades earlier than you planned. So I've spent most of my time mountain biking and riding on gravel country roads, at a leisurely pace, stopping often to hydrate and look around.

I play real sports, not trying to be the best at exercising - Kenny Powers

It will be interesting to see how a highly advanced civilization with mastery over genetics will view sports, specifically endurance sports. It seems like it's mostly a function of your genetics, how much of your life you're willing to dedicate to regimented training, sleeping 10 hours a night, developing an eating disorder, and, of course, how well you respond to supervised drug abuse. I like the idea that in this future we dispense with absolute performance in favor of relative performance, where the winner isn't picked by who went fastest but by who most outdid their theoretical genetic potential. In this future, as a viewer, you might also be shown which athlete most resembles your own genetic potential. Instead of being fans of the best-maintained genetic freak, you might be most interested in seeing what a version of yourself—one who sacrificed the best years of their life for generating watts with their legs—would be able to do, how deep they could dig. Sci‑fi aside, I think cycling has been negatively impacted by the professional sports attached to it.

Don't Trust the Pros

It's taken me about a decade to fully recover from the metaphorical brain damage caused by dabbling in triathlon/bike-racing in my early 20s, during which I managed to sustain permanent, but thankfully minor, damage to my shoulder (from a criterium race crash) and ankle (stress injury from running). We might not want to stop young men from injuring themselves, which would threaten the supply of donor organs. It might be a critical piece of brain development for men to deal with some form of permanent damage to their body before coming to terms with their own mortality. What I'm trying to say is that young male risk-taking has social utility, often in both the success and failure states.

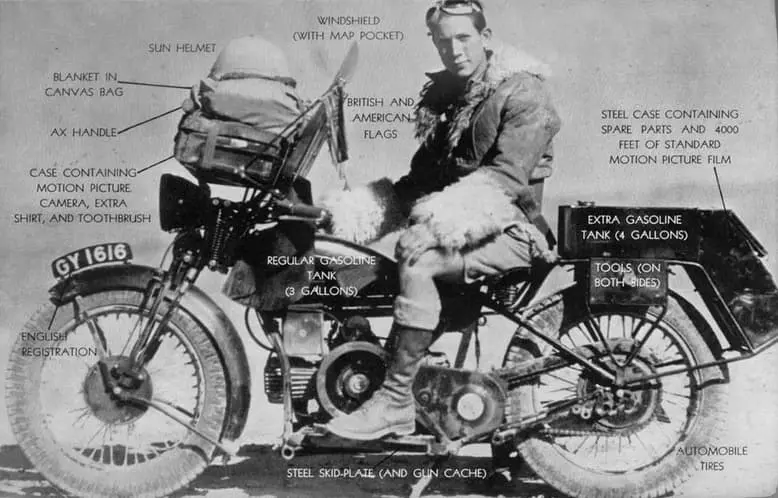

Anyways, if you are reading this, you are not a pro. So stop listening to pros. You can listen to me because I am an experienced novice—no survivorship bias here because I never survived in the first place. If you want to get the best from the most efficient means of human-powered locomotion ever invented, you need to stop trying to be like a pro and you need to try to be like this guy:

Smiles-per-Mile

Get rid of your speedometer, wattmeter, and cadence sensor—you don't need that shit where we're going. Confuzers Computers are for work time, not play time (Someday VR and AI might be able to properly simulate having explosive diarrhea in the backcountry, but today is not that day). Bring your phone and, if you want, a basic GPS unit—things that will give you assurance that if you do get lost, you most likely will not die.

The Bike

In terms of bikes, there are only two things that are really going to matter: gear-range and tires. For gear-range, you see, the key isn't to attack climbs but to enjoy gently pedaling in your granny gears as you look out and enjoy the views. You should almost never feel like any pace you are doing is unsustainable for hours on end. I've found any modern 1× MTB drivetrain works great. For tires, you want to be using tubeless; this does mean you'll be buying latex with food coloring for a 100× markup for the rest of your biking life, but it also means you won't have to worry nearly as much about random punctures that WILL happen when you go bikepacking (when it rains, it storms with tire punctures). For the tire itself, I'd use something that's like 29" and only go lower if you need to get a higher gear range (which is a function of both your gears and wheel sizes) and with a width somewhere between 2.2" to 2.6", depending on the route conditions (how much sand), with a casing that's considered durable but not something that they put on city bikes. For the tread pattern, I'd avoid any big side lugs and only moderate, normal running tread (you won't be cornering hard while bikepacking); I'd rather go with a narrow tire without lugs than a bigger one with them. In general, having a tire that's going to be a little faster but more prone to tearing/puncturing is never worth it, so just don't bring that "race casing" tire.

Geometry—now this is where the smiles-per-mile philosophy starts to come into play. Are you 5'6", weigh 145 lbs, and trying to win the Tour de France? No, well then stop buying bikes like you are; aero doesn't really matter until you're going above 18 mph—which, I hate to break it to you, is almost never going to happen when bikepacking. How do you like 6–10 MPH? Because that's where you're going to be, buddy. So leave those drop bars and aggressive geometries to the sickly bodies of the blood dope fiends. Let's get something that puts your body in a nearly vertical position; I personally opt for a hardtail mountain bike with a rigid fork, the shortest stem possible paired with swept and raised moto bars. For reference on where your body position should be, look at the Apex Cycling Predator pictured above.

Saddle. Big Chamois has been in bed with the saddle manufacturers since the beginning of time. If you like putting on wet diapers in the morning, don't let me stop you from doing that—but on the off chance you don't want to be putting on cold, wet spandex when you go bikepacking, this is where you're going to want to spend your hard-earned cuck bucks on some technological marvels. I know bike tourers swear by Brooks leather saddles; I once met some Mennonites who were riding from Patagonia to Chicago and they were all using them but had to keep them wrapped in plastic because they were struggling to keep the leather supple due to the rain and sun exposure. I can't really endorse the Brooks saddle since I've never used them and, in principle, I don't trust 1800s technology with my tender cheeks (but I understand why Mennonites only trust 1800s tech). The Brooks saddles probably work if you break them in correctly and maintain them properly, but both of those things require work—and I'm lazy. Instead, I'd HIGHLY recommend that any big body look into the Ergon Core saddles, which have way more compliance than normal saddles due to the "ice cream sandwich" design (us big bodies should be well versed in ice-cream-sandwich technology). I fully expect that these saddles do not last as long as normal saddles, but neither does a chamois—and you don't need one with this saddle, in my opinion. Secondly, if you're still feeling some tender cheeks, you can look into suspension seatposts. Cane Creek makes a few; I've been using the eeSilk+ for a while and have been happy with it. I have found that with these two bits of technology I've been more comfortable than I ever was with a chamois and traditional saddle/seatpost.

Pedals. Use flats. You're going to be hike-a-biking, and clipping in and out will be annoying. When you stop to eat 2 burritos for lunch, you will want to walk like a normal human being. Don't prioritize rigid shoes; at most you should only ever be putting down like 300 watts and only for very short periods of time. The rigid shoe will not help you. Wear whatever will be comfortable for the conditions you will be riding in—for me, that means sneakers or sandals.

Alright, that's it—nothing else about the bike really matters other than those things. Have fun with it, pick some fun colors and materials, and express your special-snowflake self!

The Gear

Alright, you've got a bike; now you need to pick what gear you need to go camping and how to attach said gear to your bike. It might be tempting to go down to your local Recreation Expense Institute to buy some overpriced dinosaur squeezings, but I would instead recommend you go onto the modern marvel website Amazon.com and buy some tactibro gear and High-Grade-Chinesium from our favorite nerd-turned-sex-addict Jeffrey Bezos.

Outdoor-Rec exists in a super position of both sincerely making quality goods that can last and cheap shit that's bad for the environment and your wallet. Mostly these days it's the latter; you need to internalize that "ultralight" is marketing speak for "will not last" and/or "made of some material that will be internationally outlawed in a few years." That's not to tell you not to buy ultralight gear, but we're going to be strapping all your gear to your bike frame, so carrying around extra weight doesn't really matter.

Sleep Setup

Sleepy time can either be your happy place while bikepacking or a long, dark hell of cold and damp. Unfortunately for you, there is no single setup that is going to work well in all conditions. For me, I've found the following to work well. If it's humid and/or rainy, bring a one-person tent; if it's dry and/or cold, bring a bivy—ideally one with some soon-to-be banned material that breathes better. I am a side- and stomach-sleeper, so for a pad I'm always bringing an inflatable pad. I bring a pretty substantial pillow. I would recommend using a synthetic bag/quilt for warmth unless you're going deep sub-zero temperature. Why synthetic? Because it works when it's wet—which is going to happen to you eventually—and being cold is the best way to ruin your night, especially if you're in a bivy where condensation will happen and easily knock 10+ degrees of warmth off your down rating. Use synthetic. An insane trend that I think exists in the outdoor rec world is how much down is used—a down sleeping bag requires like 20+ geese to die for the requisite material—then, to make the down slightly water resistant, they soak it in PFAS or other flavors of highly toxic waterproofing chemicals. All so that you can have a bag that's slightly lighter and more packable at normal sleeping temperature ranges with the fun variable of sometimes not working at all when it gets too wet. You need to have more contempt for outdoor gear companies. Anytime you walk into an REI, you need to feel like you're going to war, entering the belly of the beast. You need to be mil‑surplus maxxing.

Outdoor Rec companies have to pursue a different design philosophy than what the military uses because otherwise they would be trying to make products in a market where every year the military liquidates hundreds of thousands of articles of lightly used gear at 10% of their cost to surplus buyers. This, more than anything, is why "ultralight" is so venerated—it separates outdoor rec gear from mil‑surplus tactibro gear. Nothing about the military is ultralight, but it is durable and it works (and it will give you a back injury). Your mission is to find balance between these two: durable but without the back injury, comfortable but without spending $1000 on a sleep setup that requires spilling the blood of an extended family of geese while creating a small environmental disaster. You can do it. I believe in you.

Anyways, sleep setup:

- one-person tent and/or bivy

- insulated inflatable pad

- synthetic 30‑degree quilt

- a nice camp pillow

- head-to-toe base layer, balaclava, long-sleeve, long-johns, socks

Food/Water

Bikepacking is mostly about maintaining the correct hydration and nutrition. If you're biking for six hours a day and not consuming enough water, electrolytes, and sugars, you WILL bonk. If you aren't going to bed with a tummy full of protein and fat, you WILL get bad sleep. Maintaining the steady functioning of your digestive system is the most important thing to direct your brain power towards while bikepacking. That means:

- Planning out and following a hydration/feeding schedule (a bottle an hour, a gel per 20 miles, etc.)

- Making sure any water you drink is clean (filtering/double treating and being overly suspicious of water sources)

- Using lots of hand sanitizer before you eat or prepare food

- Carrying extra snacks—when you're hungry, you should always have something to eat

If you stray from the golden path of hydrating/feeding or do something to disrupt your digestive system, like getting food poisoning, your body will shut down. Take the extra effort and time to get these things right; feeding the machine is what you should use that brain for.

When you do get the luxury of stopping at a restaurant for a meal, my advice is to eat an uncomfortable amount and drink as much sugar water as possible (sweat tea/horchata are my preferences); afterwards, you will need to be extra careful to pick a slow pace that will aid your digestion, but ultimately those big meals will be worth it. Drinking alcohol at these stops is never a great idea—but only really a big issue if you're biking in the hot/dry, where it will definitely mess up your hydration; save it for the evenings.

In the evenings at camp, you will sleep better if you have a hot meal with lots of protein/fat, whether that means eating out of a freeze-dried bag or doing your own elaborate chilli-mac—both are good options. Cold dinner is a sign of defeat; you're better than that! Ultralight camp stoves are one bit of kit that's worth buying for this purpose.

I generally try to carry 50% more water than recommended by any particular route beta—route beta on sites like backpacking.com are generally written by 150‑lb waifs who are happy to exist on a diet of electrolyte mix, crackers, and mescaline. DO NOT TRUST ANYTHING THEY SAY. If they recommend carrying 4 liters, carry 6; if they say the route is moderately challenging, get ready to spend half of your time hike‑a‑bike. In terms of where to store that water, I'd recommend getting a 3–4 L flexible dram to put in your frame bag, some 1–1.5 L bottles to strap to your frame, and a 750 mL squeeze bottle that ideally should be usable when you're on the go.

TL;DR:

- Have more carrying capacity for water than you think you need.

- Filter/treat water more than you think is necessary.

- Eat a hot meal in the evenings as often as you can.

- Have a hydration/feeding schedule that you follow during riding hours.

The Bags

Bikepackers have a bag fetish. They love an opportunity to pay hundreds of dollars for bags that are at best marginally better than a $10 drybag and 2 voile straps. As a certified deviant, I have struggled with this and have unfortunately spent way more money than I would like to admit on bags that almost never lived up to the hype. Without saying specifically which bags are absolute trash and should be avoided, I'll instead just mention the specialty items that I have used that actually are worth it:

- Top tube bags that can be opened/closed with one hand

- Waterbottle/feedbags that can be used with one hand

That's it. The only specialty bags really worth it are things that let you use them while moving; every other bag, at most, is saving you some small amount of time/convenience taking things on and off—which in my experience is never justified by the cost. Get good at being creative with voile straps. Learn the ways of the hose clamp and tube scrap. True enlightenment only exists when you reject the $300 handlebar and seatpost bags.

Another bag worth buying is a framebag, but I would say that you should just get a cheap chinesium one from Amazon. Just buy a giant one and force it in there—if it flops out the sides, it's not that big of a deal. You'll be glad to have that extra space for your heavier gear.

In closing, bags and bag systems are pure vanity—a Veblen good to demonstrate to others just how much of your life you've wasted looking at Radavist builds. I'm not saying you shouldn't buy them, but if you do know that there is no justification for it, you are a filthy little consumer piggy and you should own that.

TL;DR:

- Voile straps and drybags

- One-hand usable top tube bag

- One-hand usable feedbag

- Big, cheap framebag

Luxury Items

Ultralight has introduced a notion of "luxury items," which are better understood as "things that make this fun." Since, in theory, we are going bikepacking for fun, I would recommend bringing these items. These include:

- A camp chair (I'd suggest a Crazy Creek if you're a high-gravity individual)

- A Bluetooth speaker (you can voile this to your bike for road tunes as well)

- Fire-starting gear/materials (a small saw works wonders)

- A camera

- Binoculars (especially for stargazing)

Instead of engaging in the ultralight race to the bottom of who's best at being in a borderline unconscious trance state while shuffling around in the woods for 16 hours a day, I'd encourage you to bring things along that will help:

- Foster conversation and connection with the people you are traveling with

- Create memories for you to cherish

- Raise morale when the going gets tough

The Route

Picking a route might be one of the most challenging tasks for a newbie bikepacker. But thanks to modern technology, we now have tools like RideWithGPS and sites like bikepacking.com that are getting new riders to bite off more than they can chew better than ever before.

The issue with finding routes is that most people who publish them are folks who work in the bike industry or are professional riders. This group of people designs only two variations of routes: routes that they enjoy at their own level of fitness and routes they enjoy while taking edibles. This means that you, the average person, shouldn't under any circumstance trust anything you see these people publish. And so whenever you're using a route provided by this type of person, you should make sure that there are plenty of shortcuts, bailouts, and bandit camp options along them, and go in assuming everything is 50% harder than they claim.

Another option, which requires some luck, is to find your Jerry. Jerry is a man in Michigan who's put together some of the most perfect routes I've ever ridden. Jerry is an everyman who takes pride in a job well done and, through a convoluted system of route-sharing, his masterpieces have landed at my feet a few times.

Jerry giveth and Jerry taketh - local proverb

You see, with a Jerry not only are you getting routes perfectly calibrated to a normal person's fitness level, but they are also likely to include some of the best unmarked campsites in the area—true gems that make the effort it took to get there worthwhile. These are places that aren't put on websites for anyone to see, and they shouldn't be, since most likely they can only handle the traffic of a handful of people using them each season. Jerry understands that the purpose of a ride is not just to grind miles but to stop and enjoy the place you're traveling through.

Find a Jerry—I don't have any great advice on how, but you are likely only a handful of Strava follower jumps away from one.

Conclusion

I've spent way more time on this journal than I thought I would; it turns out I care more about this topic than I originally thought. It's been a great way for me to spend time with people I love and make memories (most good, some bad) with them. I'm glad it's something that I ended up getting into.